Of Urdu digits and CSS counter styles

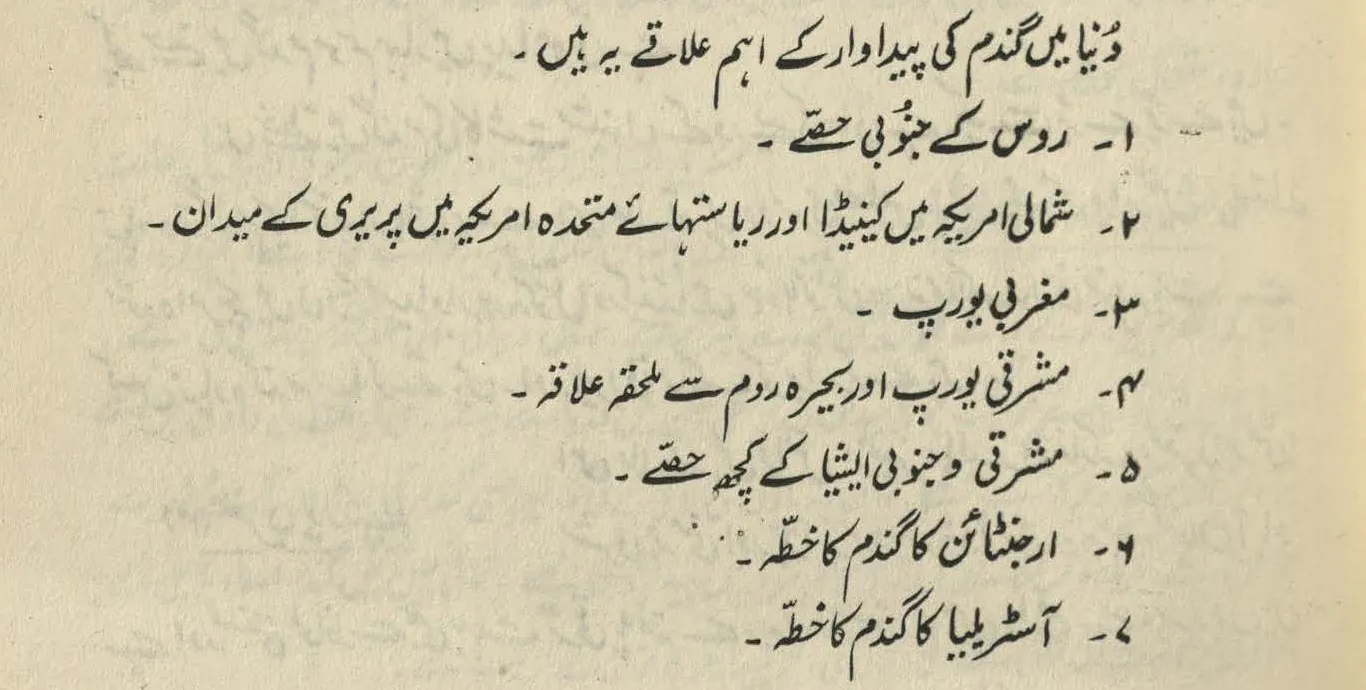

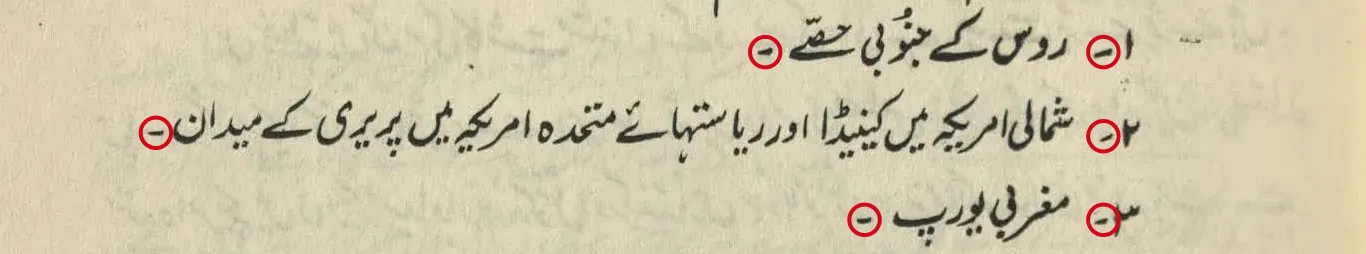

Imagine a numbered list in Urdu. Something like below:

The list items use Urdu digits as their markers, which are on the right because Urdu is written from right-to-left. (Source: a 1989 geography textbook for classes 9 and 10.)

Next, imagine that we need to implement this list in HTML and CSS. Where do we start?

The HTML part is simple—use the good old <ol>:

<ol class="urdu-list" dir="rtl">

<li>…</li>

<li>…</li>

<li>…</li>

…

</ol>

Note the dir="rtl" attribute: Urdu is a right-to-left (RTL) language, so this attribute sets the correct directionality of our list. Usually, if the whole page is in Urdu, we would add the dir attribute to the root element (<html>), but here, I have added it to the <ol> itself for simplicity.

Next, we need Urdu digits for list markers. The usual way of doing this is through the list-style-type CSS property, so let’s use it:

.urdu-list {

list-style-type: persian;

}

“Hold on,” you say. “persian? Isn’t this Urdu?”

“Yes,” I reply. “Let me take you down a rabbit hole.”

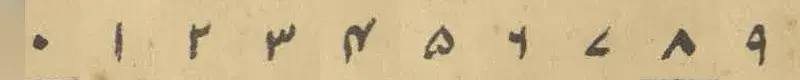

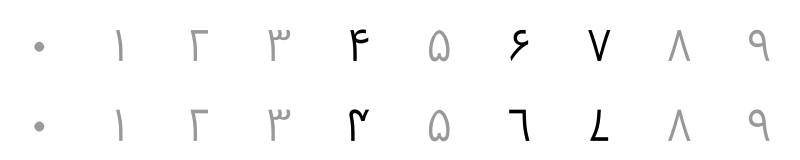

Urdu is written in the Arabic script, and the Arabic script uses the following symbols for digits:

0 to 9 (from left to right) written in the Arabic script. (Source)

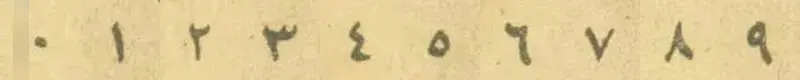

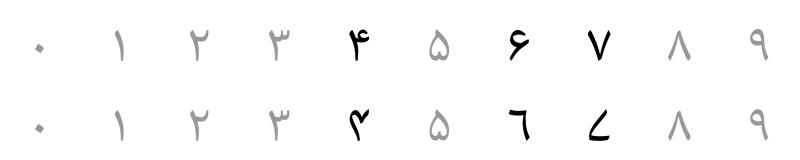

Depending on the language, some of these digits have a different shape. Examples include (but are not limited to) Persian and Urdu:

(i) Digits in Arabic language (same as the last picture).

(ii) Persian digits. (Source)

(iii) Urdu digits. (Source)

0 to 9 (from left to right) in (i) Arabic, (ii) Persian, and (iii) Urdu languages. The digit 4 has a different shape in each language; and the digits 5, 6, and 7 have different shapes in Arabic, Persian, and Urdu, respectively.

All the digits in the images above were handwritten by a calligrapher or a scribe. [1] Today, however, we write on our phones and computers, where all characters (letters, digits, punctuation, etc.) come from a global standard called Unicode. Within Unicode, there is an “Arabic block” for languages written in the Arabic script, and within that block, there are two sets of digits:

- Arabic-Indic digits, for Arabic (the language), and

- Eastern Arabic-Indic digits, for other languages that use the Arabic script (like Persian, Urdu, etc.)

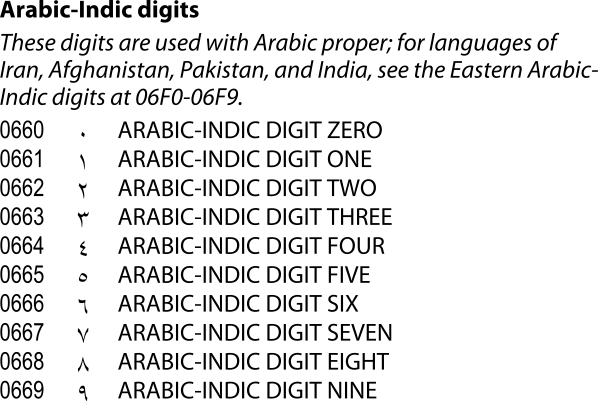

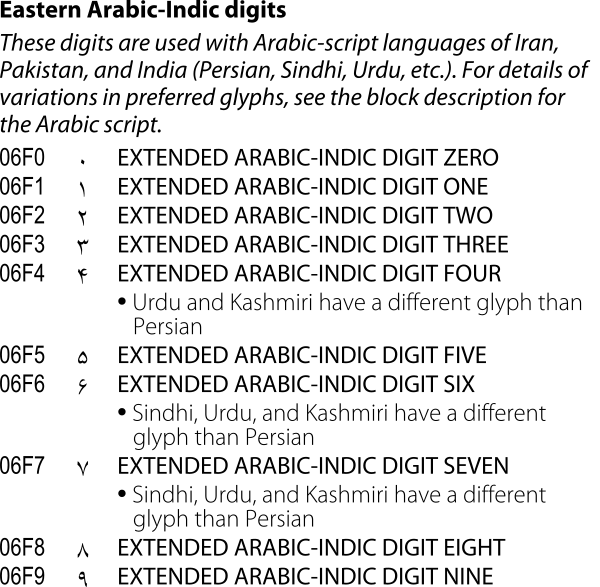

Here are both sets as they appear in the code chart of Unicode’s Arabic block:

Arabic-Indic digits. Used with the Arabic language.

Eastern Arabic-Indic digits. Used with Persian, Urdu, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and other languages of the Arabic script.

Unicode assigns each character a unique hexadecimal number called a code point. Above, Arabic-Indic digits have the code points 0660–0669, and Eastern Arabic-Indic digits have 06F0-06F9. In technical documentation, a code point is prefixed by “U+”, so, e.g., U+06F0.

You might want to ask: why does the Arabic language have its own dedicated digits, but other languages share a set? And my answer would be: I do not know! But it also raises a follow-up question: we saw above in the images of handwritten digits that Persian and Urdu have different shapes for 4, 6, and 7, and the code chart also mentions Sindhi and Kashmiri having different shapes (or “glyphs”). So if all of these languages use the same Unicode characters for their digits, how do we ensure that the correct language-specific shapes are shown in our text?

The answer is to indicate the language of the text. In HTML, we do this via the lang attribute, which informs the underlying font and text layout engines to render language-specific variants (provided that such variants are available in the font being used). Here’s a little playground that uses the lang attribute and a suitable font (Khaled Hosny’s excellent Amiri) to show how Eastern Arabic-Indic digits change their shapes depending on the language:

Output

۰ ۱ ۲ ۳ ۴ ۵ ۶ ۷ ۸ ۹

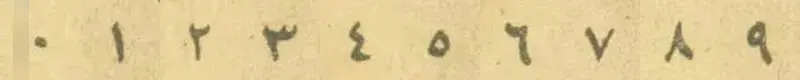

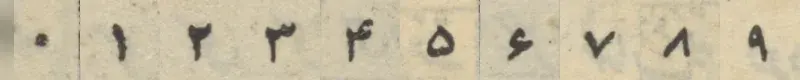

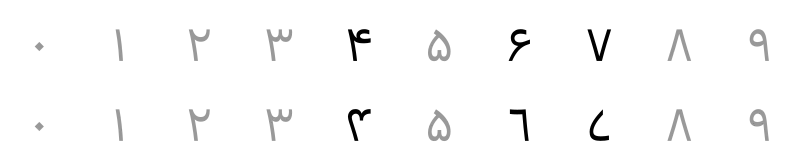

Note that when no language is specified, Amiri is showing Persian shapes. This is because Persian shapes are almost always the default in most fonts. For example, below are Eastern Arabic-Indic digits set in the default UI font for Arabic script on various platforms (in each example, top row shows default/Persian shapes, and the bottom row shows Urdu shapes that are enabled when text language is set to Urdu):

Noto Naskh Arabic, default on Android.

Segoe UI, default on Windows.

SF Arabic, default on Apple platforms. However, if Urdu is enabled in preferred languages, then Noto Nastaliq Urdu (that has Urdu digit shapes as default) is used for Urdu text—see below for a sample.

On the other hand, fonts that are made primarily for Urdu use Urdu shapes as default:

Noto Nastaliq Urdu. (It is the default for Urdu text on Apple platforms if Urdu is enabled in preferred languages).

The Unicode standard never explicitly states that default forms for Eastern Arabic-Indic digits should be Persian. However, it does use Persian shapes in its code chart, which likely explains why font makers treat these digits as Persian by default. This creates friction for speakers of other languages (like Urdu), who expect to see forms specific to their language, but encounter Persian ones instead. Modern web browsers have excellent support for language-specific forms (as we’ve seen in the playground above), but users may not always be able to indicate the text language or use a suitable font (for example, when posting on social media, where there is little to no control over formatting). [2] Outside the web (e.g., word processors, graphic design apps, or desktop publishing software, etc.), the situation is also a mixed bag, where support for specifying the language and triggering language-specific forms is either lacking or inconsistent.

In the past, this has led to proposals for encoding separate code points, but Unicode’s position is to treat such language differences as font variants. In hindsight, if font variants are indeed the right solution, there probably should have been a single set of digits for the Arabic script, and all shape differences (from Arabic to Persian to Urdu to Sindhi to others) could have been delegated to the font layer. Perhaps then, support of language-specific forms in applications (and fonts) may have been more robust, too.

To summarize—in order to use Urdu digits, we should:

- Use the correct Unicode characters, i.e., Eastern Arabic-Indic digits (U+06F0 to U+06F9).

- Use a font that has Urdu variants of the digits. Or, use a font that has Urdu digit shapes as default.

- Specify that the text language is Urdu, so that Urdu variants in the font are shown. You may be tempted to skip this if you’re using a font that has Urdu digit shapes as default, but it is still a good practice to indicate the text language.

Let’s take a break here and add the lang attribute to our list’s markup: [3]

<ol class="urdu-list" dir="rtl" lang="ur">

<li>…</li>

<li>…</li>

<li>…</li>

…

</ol>

And let’s now move towards the CSS.

The CSS property list-style-type accepts several keyword values for setting the appropriate marker of list items. The most common is decimal (1, 2, 3, …), but you’ve probably used others too, like lower-roman (i, ii, iii, …); or lower-alpha (a, b, c, …); or circle (most likely for a <ul> instead of an <ol>).

Technically, these are called counter styles. Back in the days of CSS 2.1, the CSS specification (“spec”, for short) defined a handful of counter styles, but they weren’t enough to cover the conventions of every language in the world. To address this, a new @counter-style rule was introduced [4] back in the early 2010s, which enabled authors to define their own counter styles. Existing counter styles from CSS 2.1 were also redefined to use this new syntax; for example, following is the definition of decimal:

@counter-style decimal {

system: numeric;

symbols: '0' '1' '2' '3' '4' '5' '6' '7' '8' '9';

}

(You can read more about the syntax of @counter-style at MDN Web Docs, or in the Counter Styles spec itself.)

As promising as @counter-style was, its support didn’t land in web browsers until much later (except in Firefox, which was the first to ship it back in October 2014). Meanwhile, an interesting thing happened:

The Counter Styles spec also includes a set of predefined counter styles to cater to different languages. By 2014, these predefined counter styles were being shipped in major web browsers independent (and ahead) of the implementation of @counter-style itself. [5] So while CSS authors couldn’t yet define their own counter styles, they could at least use the predefined counter styles included in the web browsers…

… and one of those styles was persian:

@counter-style persian {

system: numeric;

symbols: '\6F0' '\6F1' '\6F2' '\6F3' '\6F4' '\6F5' '\6F6' '\6F7' '\6F8' '\6F9';

}

Take a closer look at the symbols above: they are Eastern Arabic-Indic digits (U+06F0 to U+06F9)!

This means that while the counter style is named persian, it can also be used for Urdu, Sindhi, or other Arabic-script languages, because same set of digits, remember? All we need for the correct language-specific shapes are the appropriate lang attribute and a suitable font.

And thus, we come out of the rabbit hole and return to our original list, which has the following markup:

<ol class="urdu-list" dir="rtl" lang="ur">

<li>…</li>

<li>…</li>

<li>…</li>

…

</ol>

… and the following CSS:

.urdu-list {

list-style-type: persian;

}

… and which results in the following:

- روس کے جنُوبی حصّے۔

- شمالی امریکہ میں کینیڈا اور ریاستہاۓ متحدہ امریکہ میں پریری کے میدان۔

- مغربی یورپ۔

- مشرقی یورپ اور بحیرہ روم سے ملحقہ علاقہ

- مشرقی و جنوبی ایشیا کے کچھ حصّے۔

- ارجنٹائن کا گندم کا خطّہ۔

- آسٹریلیا کا گندم کا خطّہ۔

Let me now confess that I haven’t been completely honest with you…

Around the time when web browsers shipped the persian counter style (among other predefined counter styles), Chrome and Safari (both of which used WebKit back then) also shipped the non-standard urdu, and Firefox included the non-standard -moz-urdu. These two styles are identical to persian.

So if we are bothered by the use of persian for Urdu lists, we can also write for Chrome/Safari/Edge:

.urdu-list {

list-style-type: urdu;

}

And for Firefox:

.urdu-list {

list-style-type: -moz-urdu;

}

We may be tempted to combine them so that we have a single CSS rule covering all browsers:

/* Don't use this! */

.urdu-list {

list-style-type: persian;

list-style-type: -moz-urdu;

list-style-type: urdu;

}

But I wouldn’t recommend it, because it will break in an unexpected way: The Lists and Counters spec states that “[i]f the specified counter-style does not exist, ‘decimal’ is assumed”. In the above code, Firefox will ignore the first two list-style-type properties because of the cascade, and then try to use list-style-type: urdu; but because urdu doesn’t exist in Firefox, the list will fall back to using decimal. (If we instead move -moz-urdu to the end, then the same behaviour will happen in Chrome/Safari/Edge.) Therefore, the only way to ensure that we get the correct digits is to move list-style-type: persian to the end, at which point we may as well only use list-style-type: persian and not bother with the others.

But if using persian for Urdu lists still doesn’t feel right to you (and I hear you), then good news: browser support for @counter-style sits at 94% today, [6] which means that we can easily define and use our own urdu counter style:

@counter-style urdu {

system: numeric;

symbols: '\6F0' '\6F1' '\6F2' '\6F3' '\6F4' '\6F5' '\6F6' '\6F7' '\6F8' '\6F9';

}

/*

If we wished, we could also "extend" the browser-defined `persian` counter style:

@counter-style urdu {

system: extends persian;

}

Either way, this `urdu` counter style will override the browser's (if present).

*/

.urdu-list {

list-style-type: urdu; /* Yay! */

}

All good, but now that we’re defining our own urdu style, let’s make it even better.

Notice that in the image of our original list, each Urdu digit in the list marker is followed by an Urdu full stop:

Urdu full stops highlighted in red (after each digit in the list marker and at the end of each sentence). Notice that the full stop looks less like a dot and more like a small horizontal stroke. It also has its own code point in Unicode: U+06D4.

The @counter-style rule lets us specify the prefix and suffix—i.e., content that will be added to the beginning and end, respectively—of the list markers. By default, prefix is an empty string, while suffix is a Latin full stop (.) followed by a space. (If you look at the output above where we used persian as our list’s counter style, you’ll also see the Latin full stop.)

Let’s, then, update our urdu style to use the Urdu full stop as the suffix:

@counter-style urdu {

system: numeric;

symbols: '\6F0' '\6F1' '\6F2' '\6F3' '\6F4' '\6F5' '\6F6' '\6F7' '\6F8' '\6F9';

suffix: "\6D4\20"; /* U+06D4 is the Unicode character of Urdu full stop. U+0020 is space. */

}

.urdu-list {

list-style-type: urdu;

}

… which, combined with our list’s markup, will give us the following:

- روس کے جنُوبی حصّے۔

- شمالی امریکہ میں کینیڈا اور ریاستہاۓ متحدہ امریکہ میں پریری کے میدان۔

- مغربی یورپ۔

- مشرقی یورپ اور بحیرہ روم سے ملحقہ علاقہ

- مشرقی و جنوبی ایشیا کے کچھ حصّے۔

- ارجنٹائن کا گندم کا خطّہ۔

- آسٹریلیا کا گندم کا خطّہ۔

And this, finally, is how we implement an Urdu numbered list in HTML and CSS.

Of course, lists in Urdu don’t just use numeric counter styles; there are other variations, too.

The W3C Internationalization Working Group maintains a document called Ready-made Counter Styles, which defines a large set of counter styles for various languages and cultures around the world (that can be reused or tweaked by CSS authors in their own stylesheets). For Urdu, there are three styles listed in that document: urdu (the same as what we defined above), urdu-abjad, and urdu-alphabetic. [7] I strongly recommend that you check these styles, too.

And I also strongly recommend to revive Urdu digits… not just in lists, but wherever we can in our Urdu texts. They are awesome.

-

There are minor stylistic differences even among numbers that use the same shapes, but we can ignore them for this post. [Back]

-

One of the things I like about Mastodon is that it lets you set the language of your posts, both globally and for a single post, and then uses that information to set the

langattribute’s proper value. [Back] -

Just like the

dir="rtl"attribute, thelang="ur"attribute also makes more sense on the root element (<html>) if the whole page is in Urdu. [Back] -

@counter-stylewas initially included in the CSS Lists and Counters module, but eventually moved to its own module (CSS Counter Styles). [Back] -

The actual timeline of the development of predefined counter styles and their inclusion in both the CSS spec and the web browsers is not as linear as I just told you, but let’s not go there for now. [Back]

-

It took a long time for

@counter-styleto reach 94%. Firefox 33 was the first web browser to support it in October 2014. After that, it took nearly seven years for Chrome 91 (and Edge 91) to include it in May 2021. Two years later, Safari 17 shipped it in September 2023. [Back] -

Full disclosure: I helped a bit with these Urdu styles. [Back]