The nostalgic sewing machine manual

This was originally a Twitter thread, posted on September 17, 2022. I’ve made some edits for this post.

A while back while cleaning my father’s library, I found a battered Urdu manual for the Singer Sewing Machine (Model 109H), which my mother used to own back in the late ’80s:

Cover of the manual

I don’t really remember the sewing machine, nor do I remember seeing this manual before, but ever since finding it I’ve been fascinated by it, and often thumb through its pages for inspiration.

Let me tell you why.

First, some specifics. The manual doesn’t mention a date, but it’s safe to assume that it was produced in the ’80s. It does mention that it was printed by “Lithocraft Corporation, Karachi”:

It’s been a while since I’ve seen this old, simplified font.

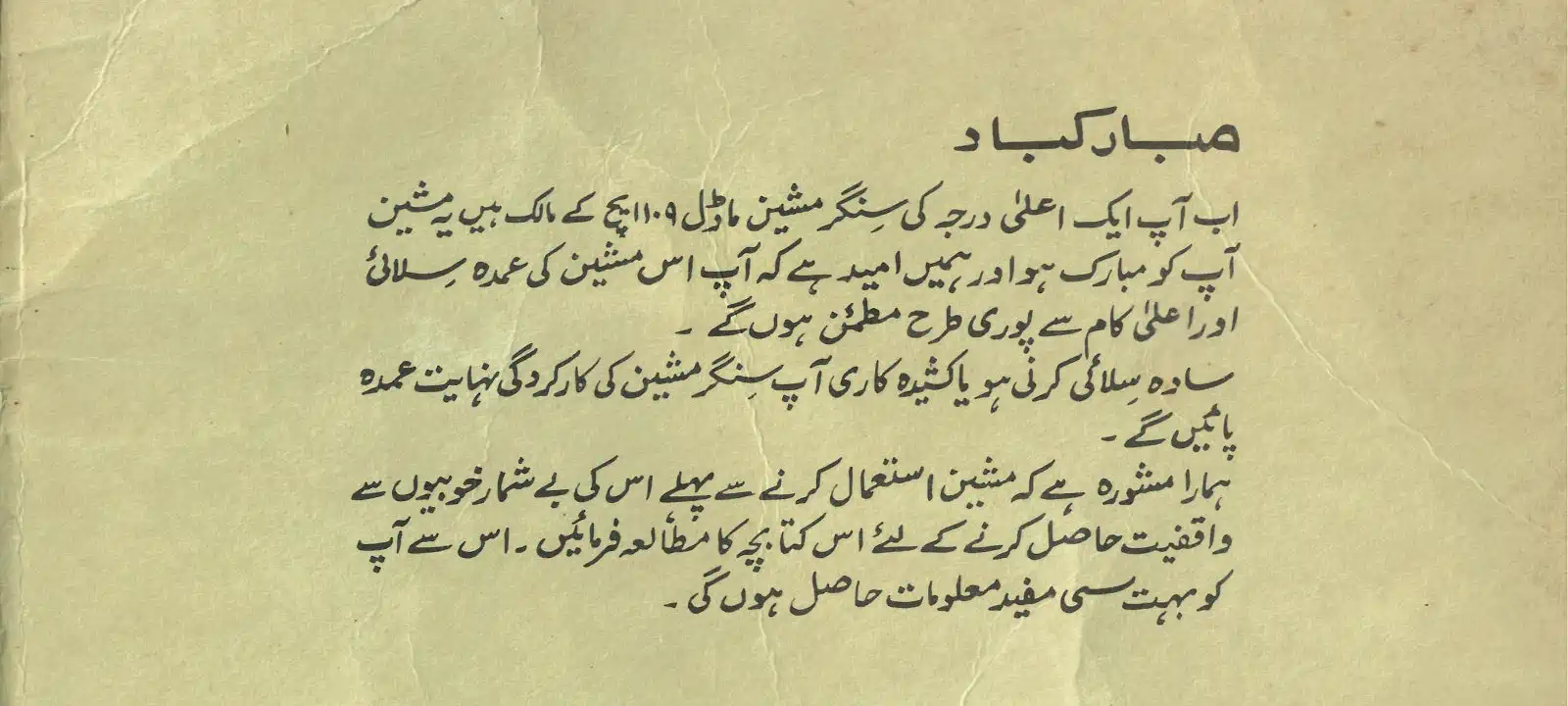

Interestingly, this note about being printed in Karachi is the only thing that is not handwritten. Everything else in the manual is scribed in Dehlvi nastaliq, with some Indian naskh (a simplified flavor of it) sprinkled for headings and emphasis:

But being handwritten is almost expected, given the manual’s age. It’s the other design elements that stand out to me…

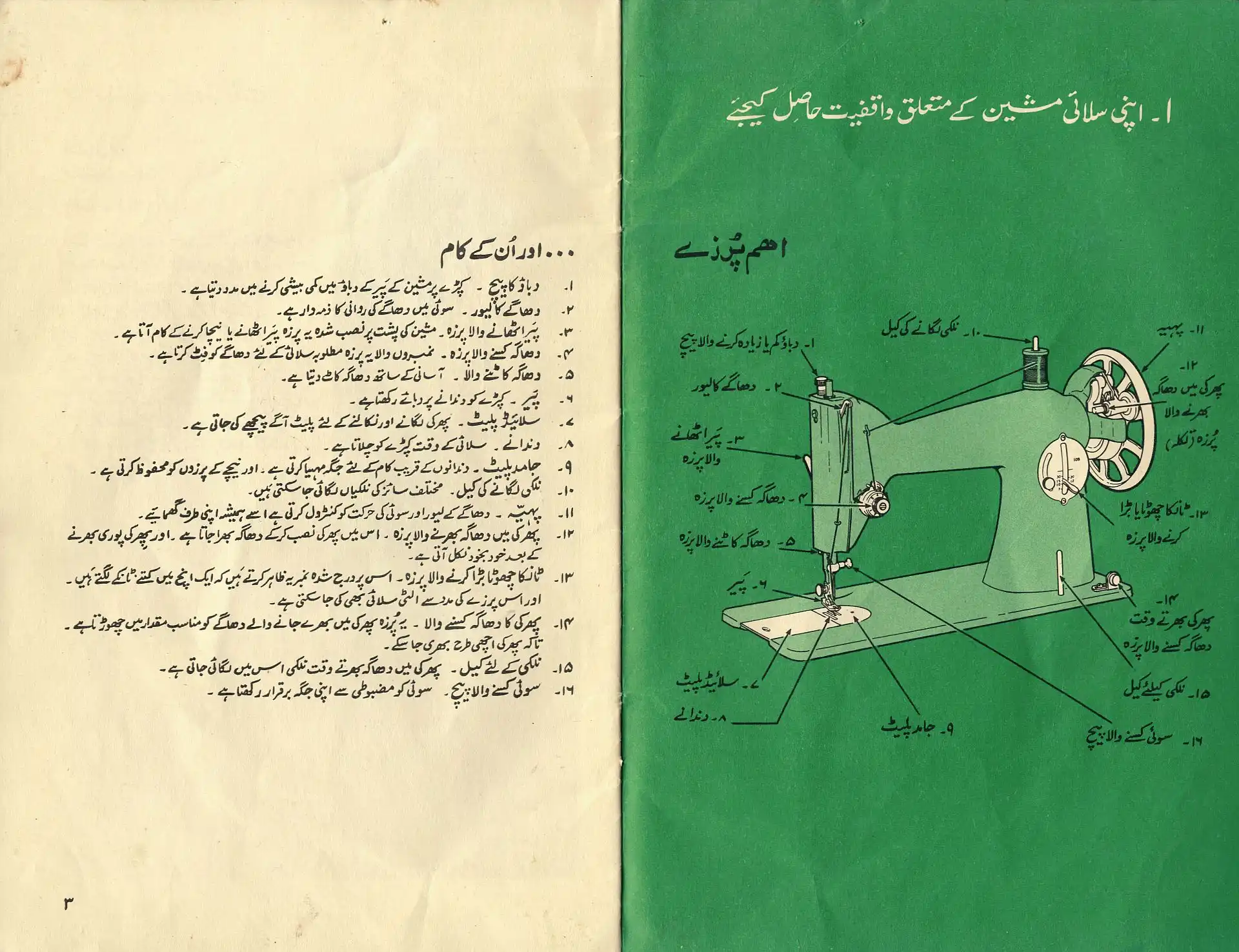

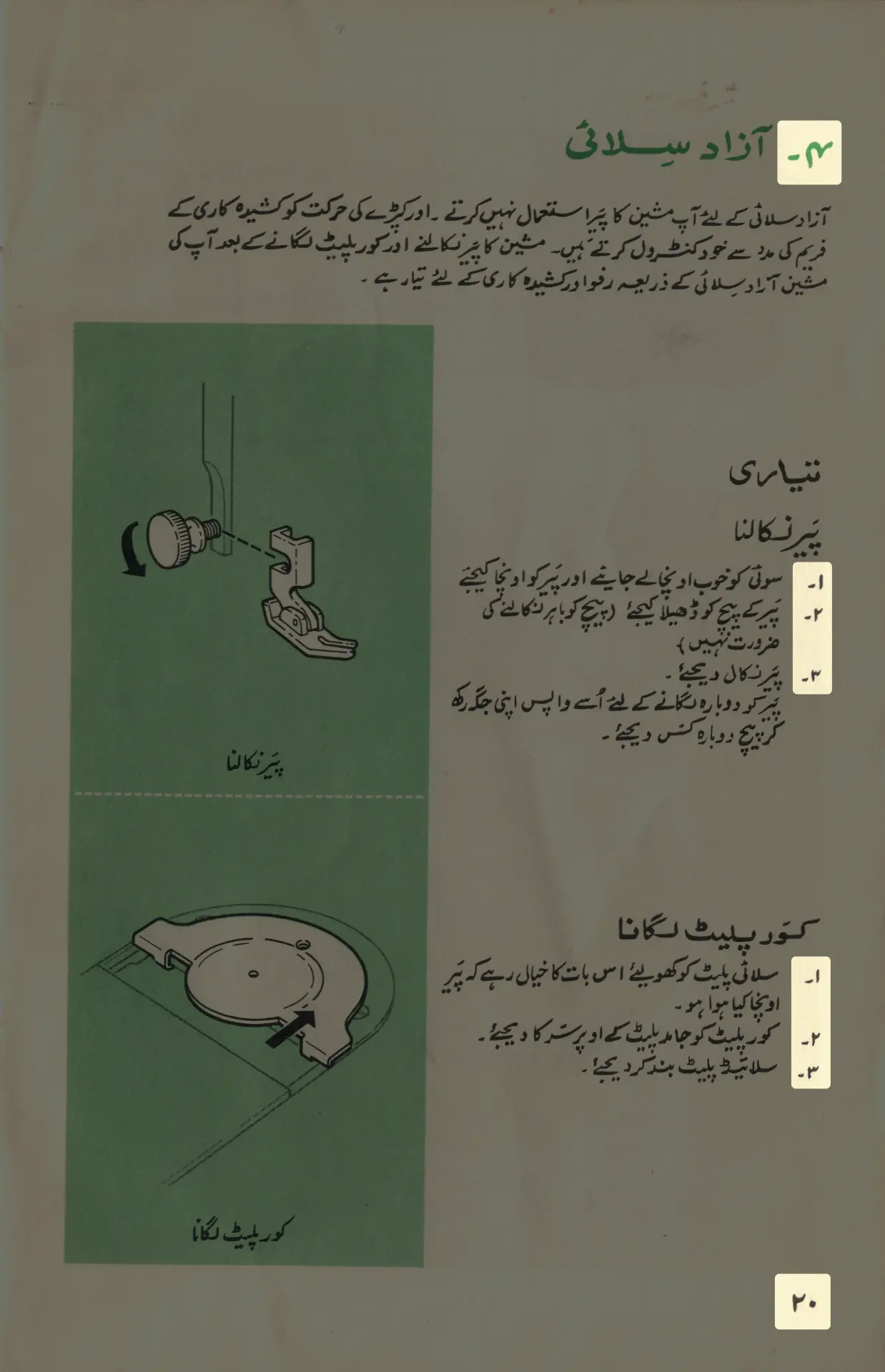

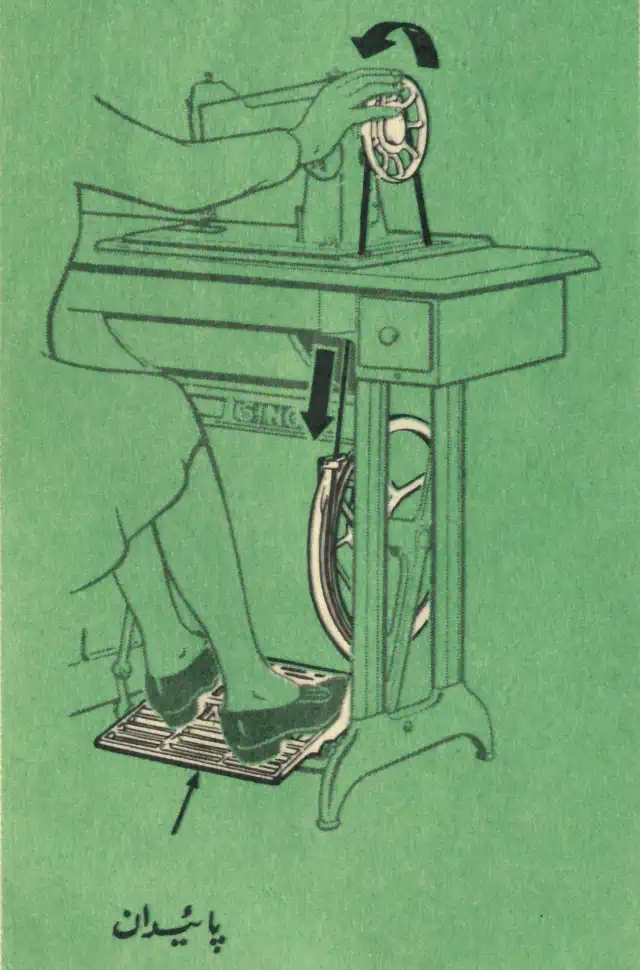

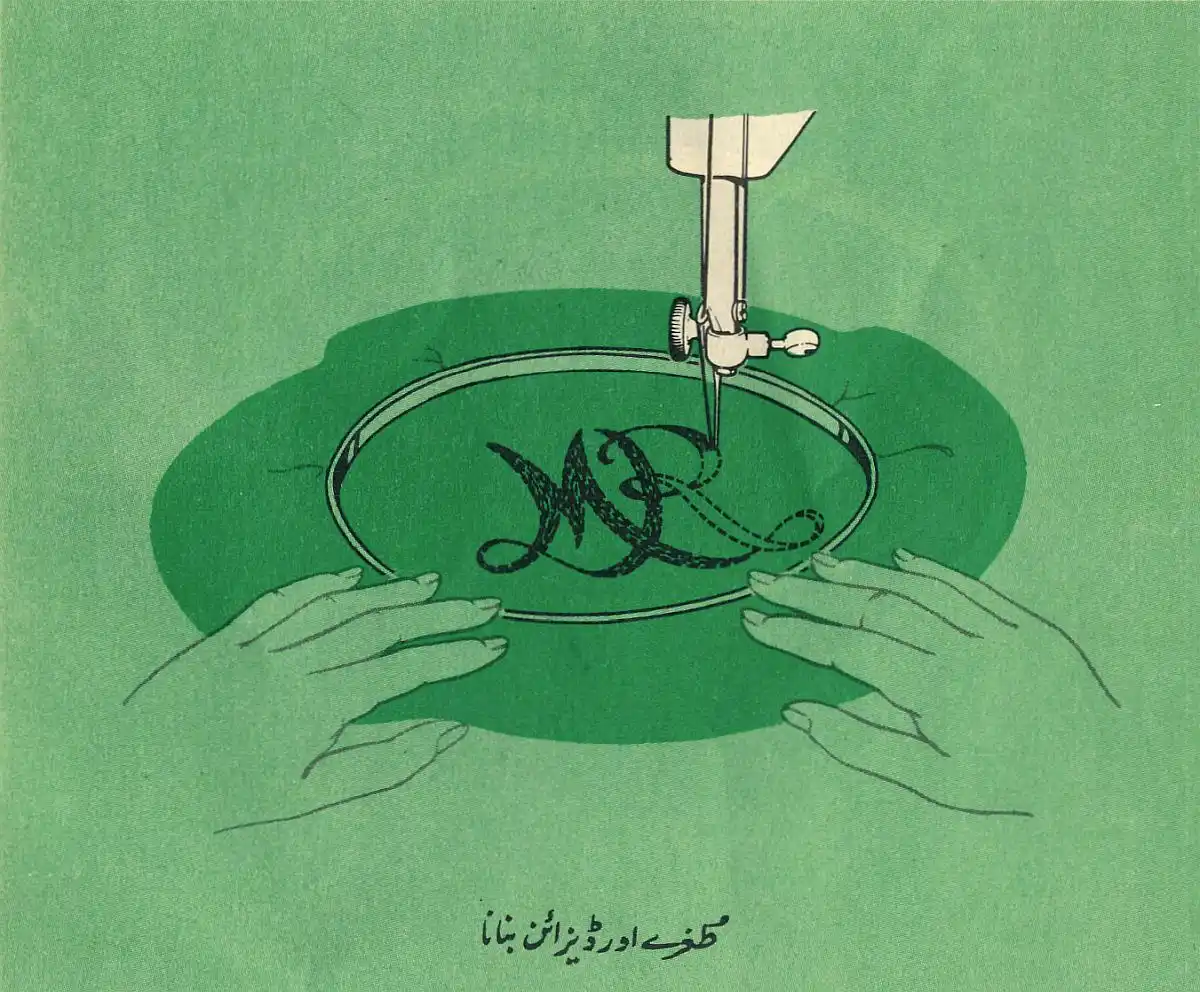

First, its striking use of color, which is a rarity in the modern, black-on-white manuals we usually get in Pakistan. I mean, just look at this spread:

This spread is where I fell in love with the manual.

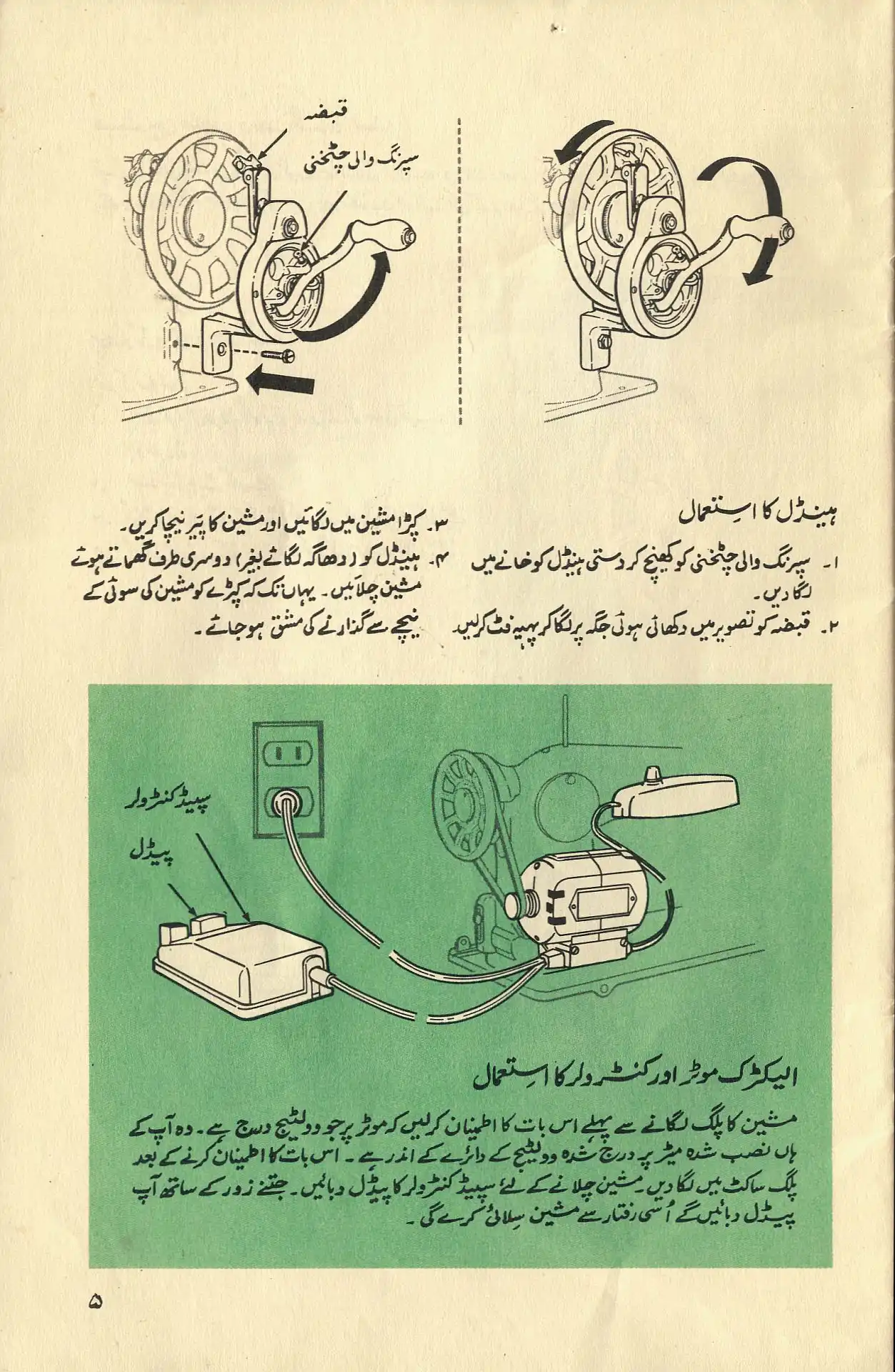

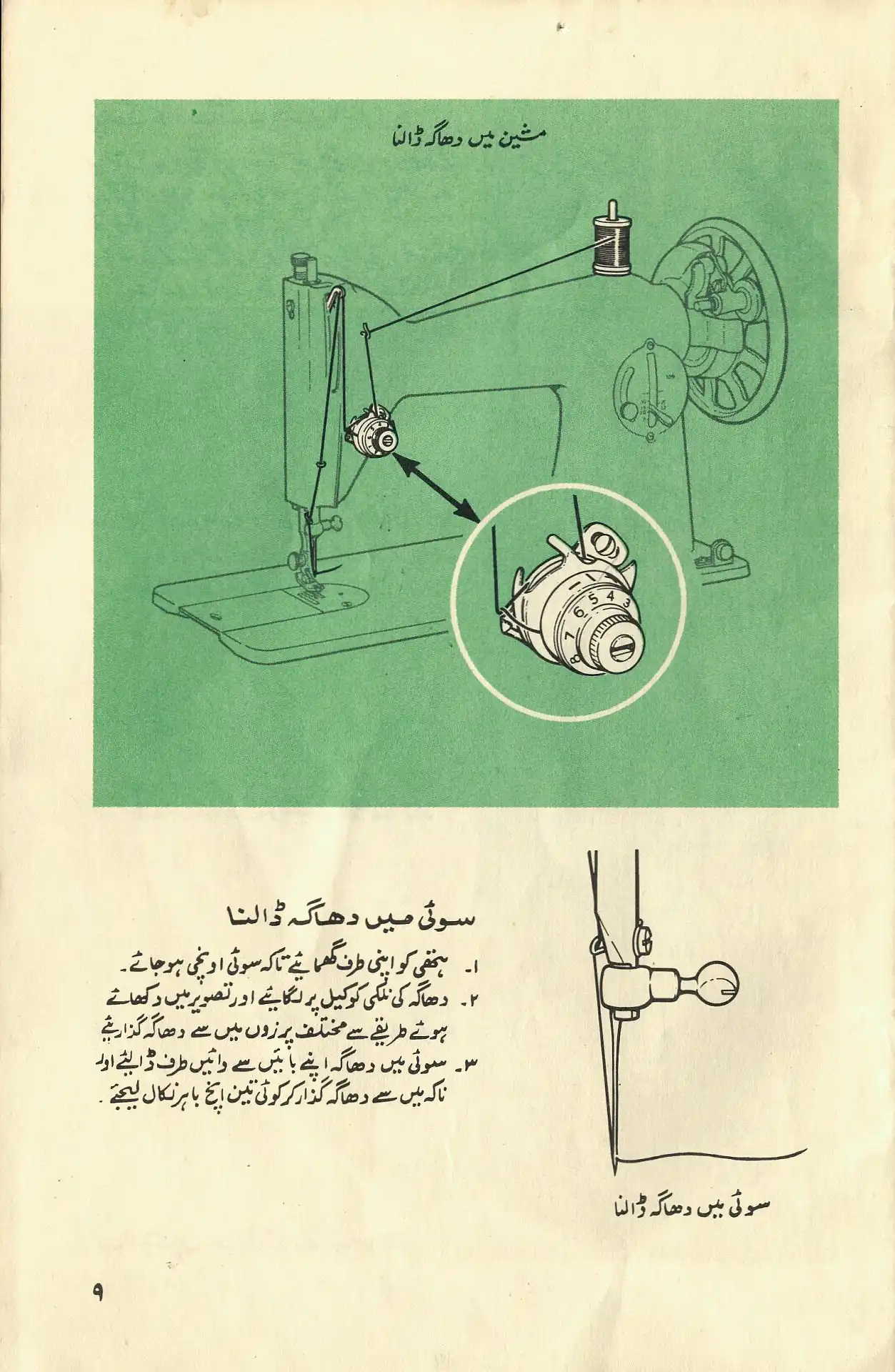

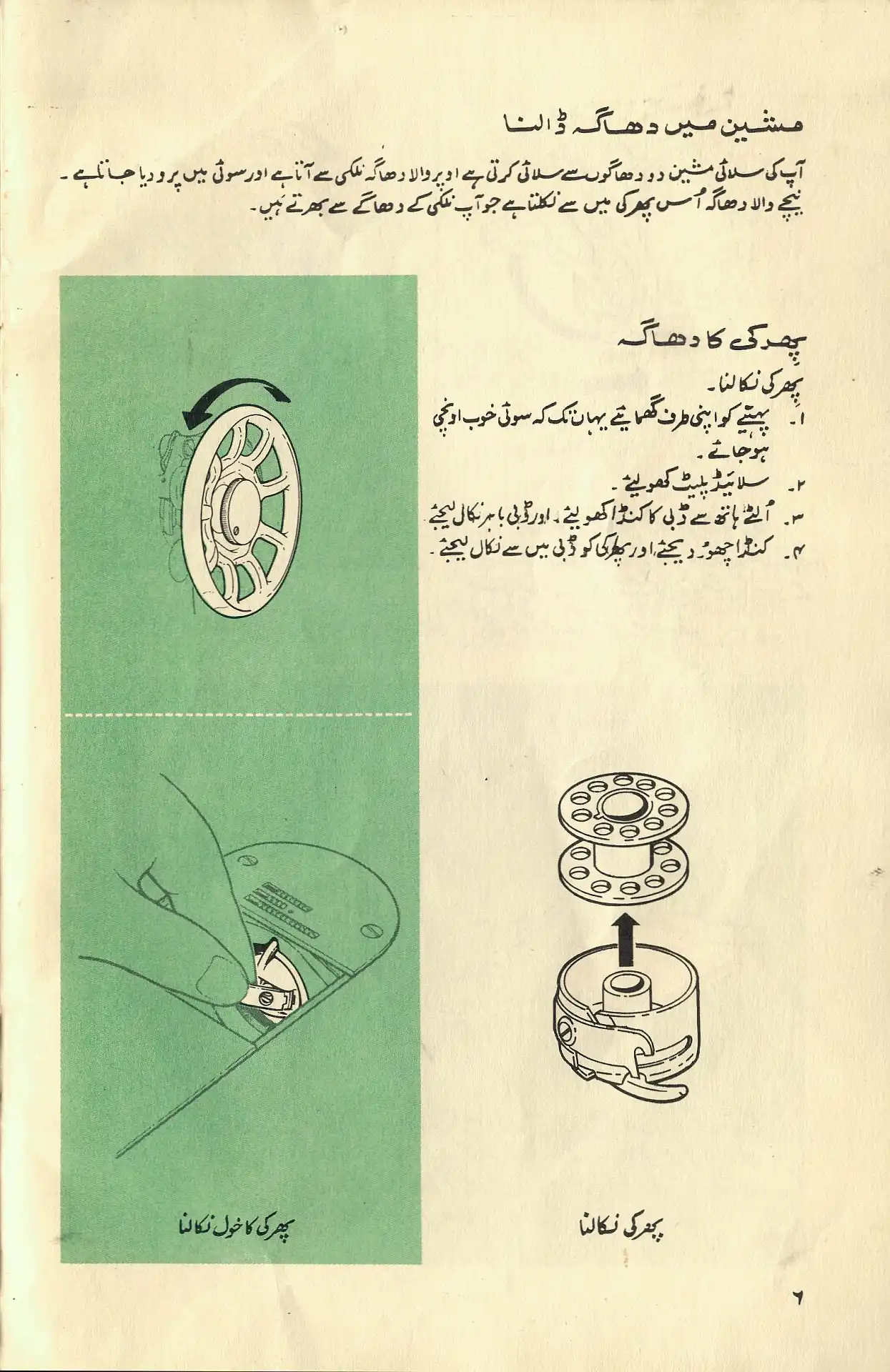

The manual also utilizes color for highlighting specific parts in its many diagrams. A few examples below:

Next: Urdu digits, which are gradually (and sadly) falling out of use in today’s Urdu media. Even I have neglected them on a few occasions, despite being their big fan.

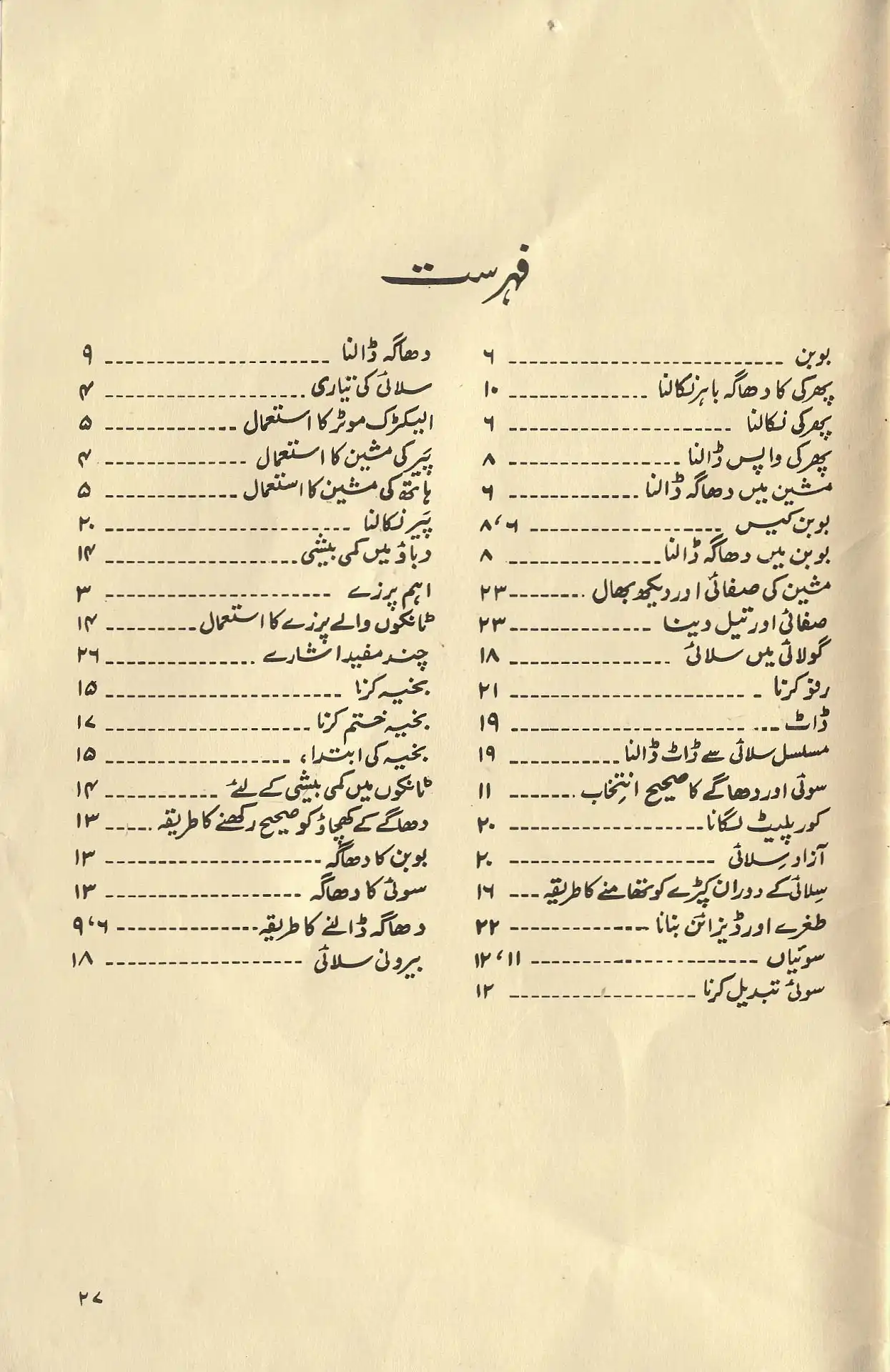

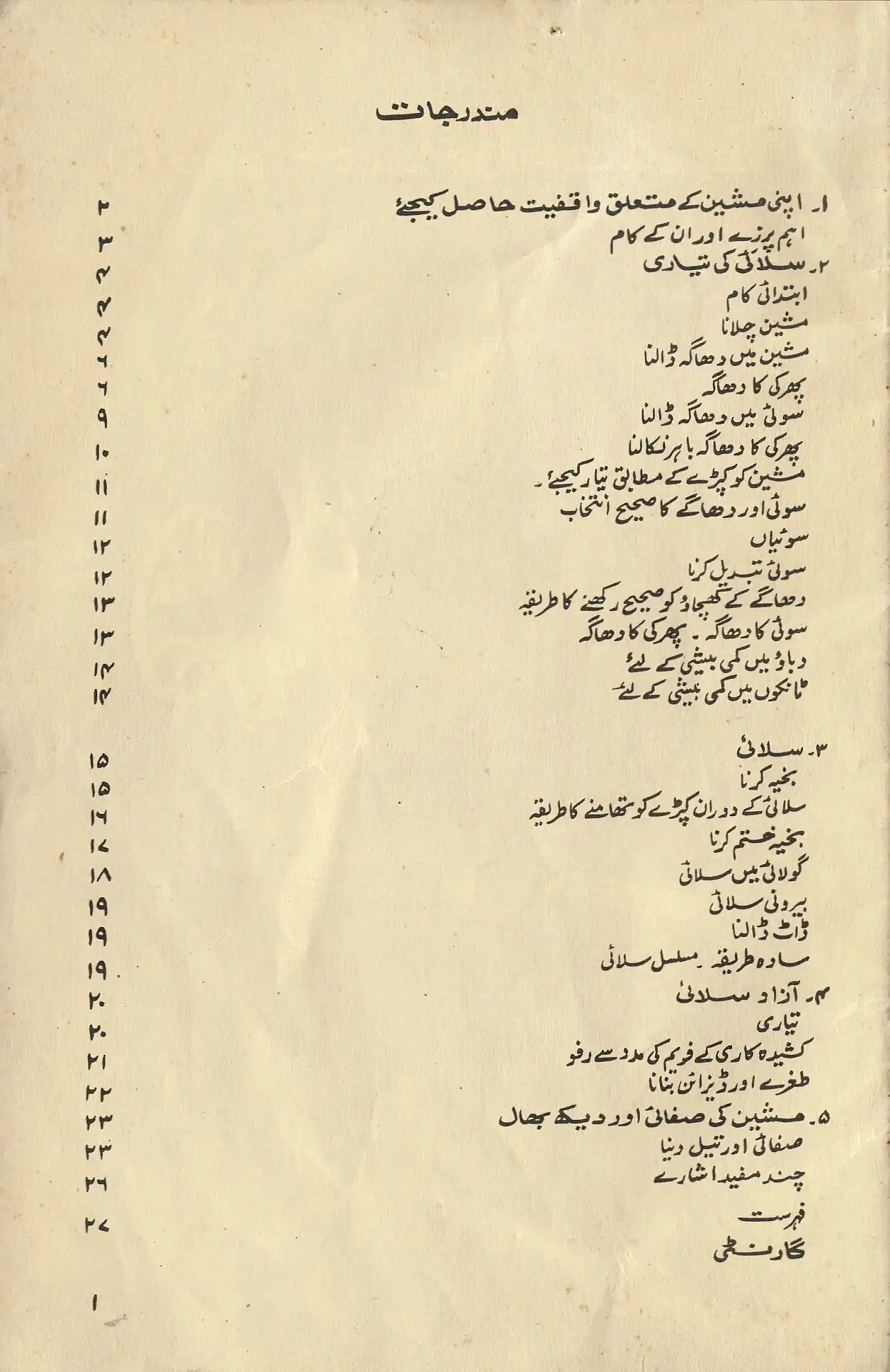

Most Urdu books do not include an index at the end (which they should, in my opinion), but this little manual does. Curiously, its index entries are not sorted alphabetically, and the title is “فہرست”, which I’d normally use for a table of contents. And speaking of table of contents, they are titled “مندرجات” in this manual:

Index of the manual

Table of contents

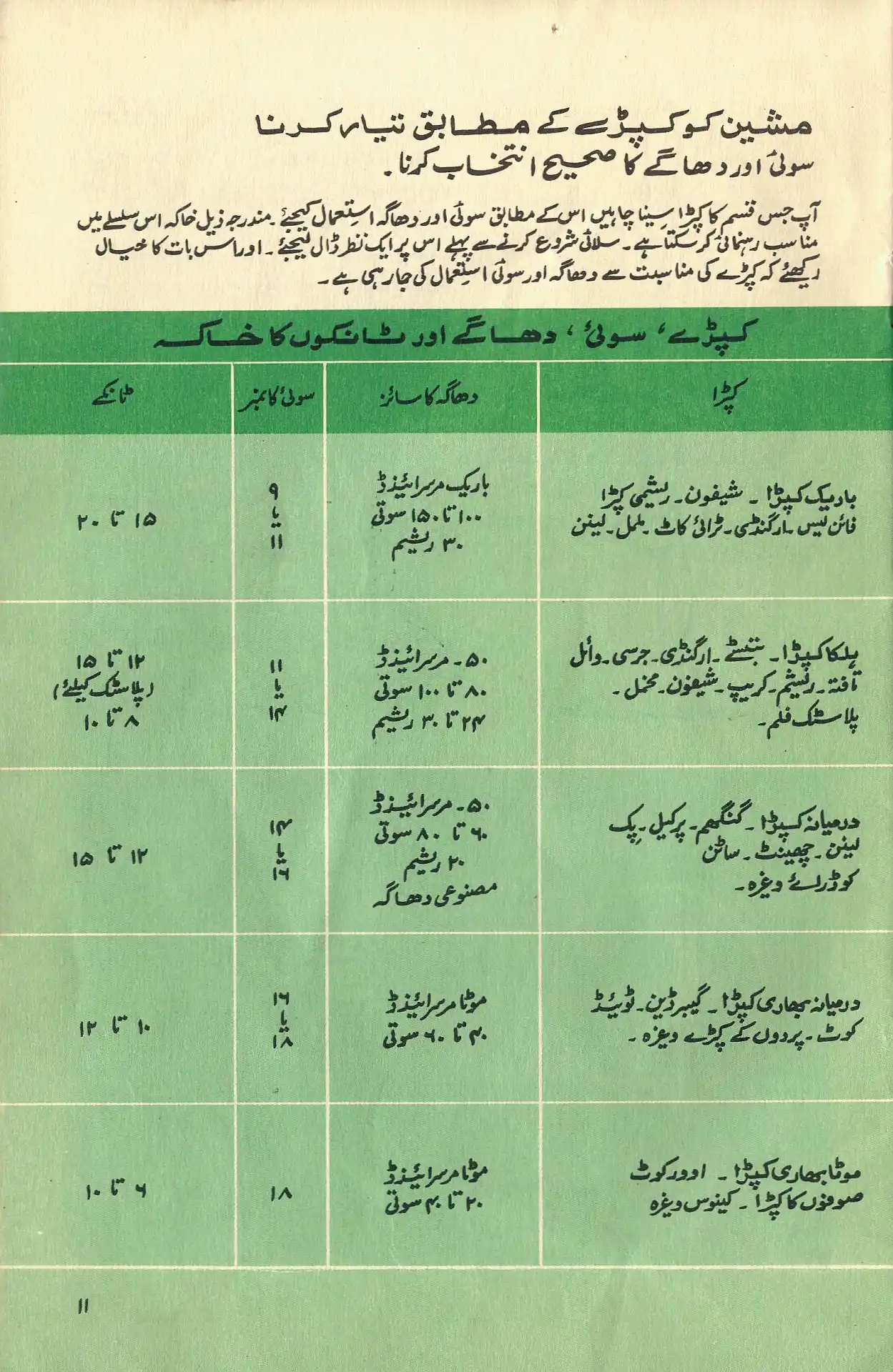

The following page shows a bit of everything—a nice, clean table layout; naskh for creating hierarchy; elegant use of color; and Urdu digits:

A couple of illustrations suggest that they (and possibly the colors and layout, too) may have been copied from an English or Western counterpart (which I couldn’t find in my father’s library or anywhere on the web):

Even then, Singer deserves the credit for thoughtfully adapting the source material for their Pakistani audience, instead of churning out an uninspired copy void of any character (which is sadly the norm these days for user manuals).

For those who’d further like to bask in the glory of this nostalgic manual, 🙂 I have uploaded it on the Internet Archive.